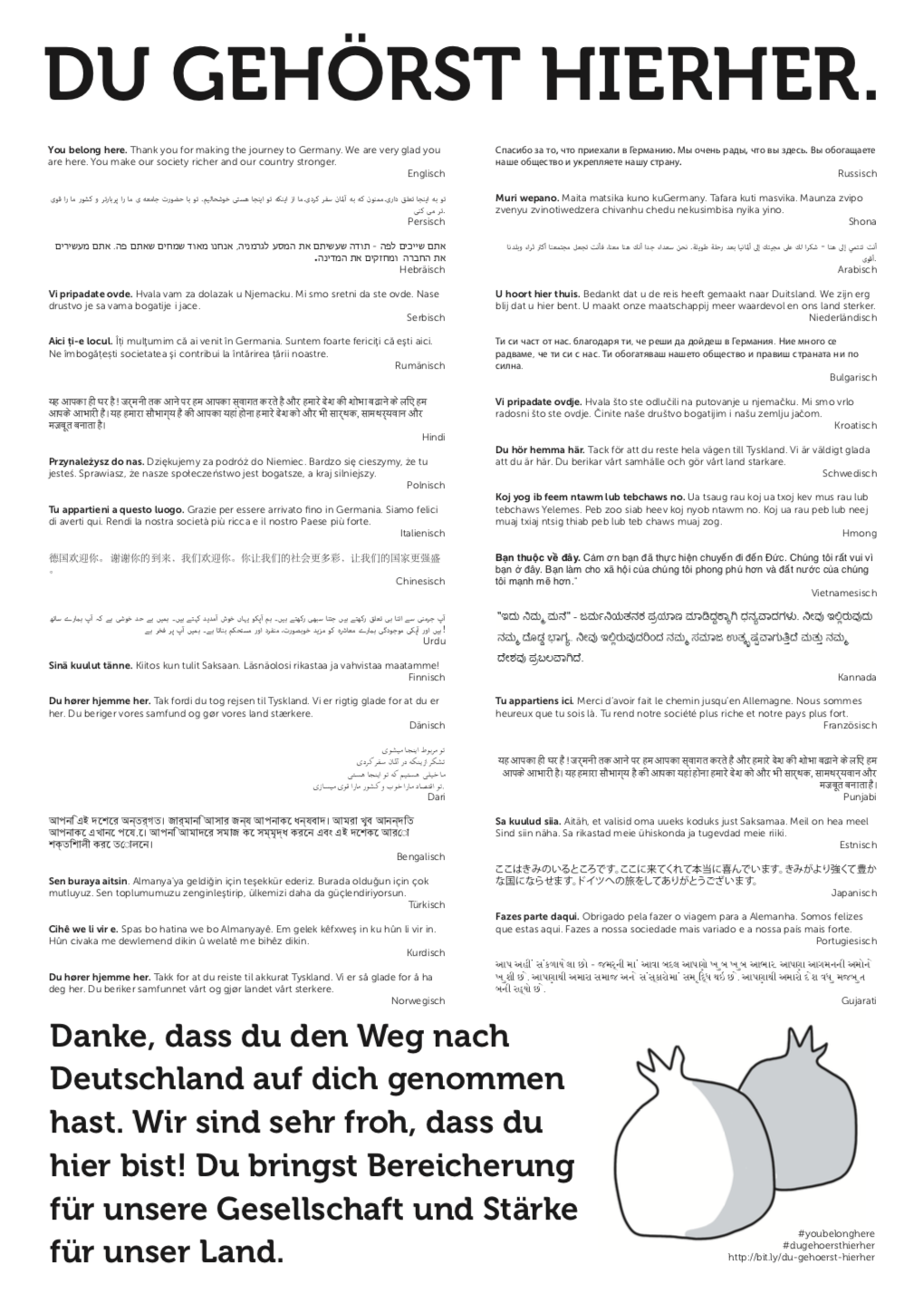

This is a simple poster campaign to let foreigners know, in their own language, that they are welcome in Germany. If you would like to download the poster and put it up in your city, school, university, or workplace, it is available here:

- PDF format (A3)

- Adobe Illustrator, in case you would like to change the text, correct spelling, or add languages

Why this matters now

About two weeks ago, a friend and I noticed a poster in the Westkreuz S-Bahn station in Berlin that advertised the German government’s financial support for “Freiwillige Rückkehr,” or voluntary return for immigrants. These posters bear the logo of the BMI (Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat) – roughly translated as “ministry of the interior.” The poster states that, if you apply by 31 December 2018, Germany will also cover 12 months housing costs in your homeland.

The heading on the top says, “Your country, your future, now!” Imagine how that sounds to somebody whose country is in ruins. Imagine how that sounds to someone who made the dangerous journey to Germany because it was their only chance to even have a future.

I actually think it’s okay that the government will provide immigrants with a free ticket back to their home country. The problem isn’t that Germany will buy me a one-way ticket to the US, or my friends one-way tickets to Iran, India, Mexico, what have you. The problem is that Germany wants to. This offer is being advertised like a vacation special, a limited-time offer, a get-it-now bargain. And who is it being advertised to? The languages chosen tell you all you need to know: English, Farsi, Russian, Pashto, Arabic, French (you can bet this isn’t directed at Parisians), and yeah, check out those flags on top. That’s… not exactly a random sampling of world flags and languages. Finally, as a friend of a friend pointed out, all our paperwork to live and work in Germany is in German only – but as soon as the government wants to tell us about leaving Germany, suddenly our identities are acknowledged and we are are addressed in our native languages.

This poster campaign is wildly offensive. But it’s not the only sign that Germany’s 2015 burst of “refugees welcome” spirit continues hardening into xenophobic hostility. This summer, people all over the world read about the right-wing rallies in the city of Chemnitz, and how the ensuing rash of hate crimes have immigrants and their supporters fearing for their safety. To pick one example at a more personal level, football superstar Jérôme Boateng says the district 15 minutes north of my house is a “no-go area” for him and his daughter. There’s no doubt about it: 2018 was a pretty ugly year for a country that wants to be seen as modern, welcoming, and pluralistic.

Media outlets all over Germany have reported on these posters (for example, rbb, Hamburger Morgenpost, Stuttgarter Nachrichten, and many others). There’s already been a fair amount of of pushback, and a (super clever and well-executed) poster campaign. The only reason to add to the growing chorus of resistance is that my friends and I wanted to get together and do something concrete and visible.

Why this matters to me

I am a foreigner in Germany. My husband and I are white, American, highly educated, able-bodied, and doing well financially. We are both committed to learning German (yeah, yeah, I should have written this blog post in German, but I didn’t want grammar and usage mistakes to distract from my message). We have a lot of friends here, both German and foreign, and a strong professional network in the US and in Germany. We own our apartment in Berlin and are friendly with people in our building and in our neighborhood. I’m the perfect foreigner. Sounds great, right?

But thanks to hints like this poster, I often get the feeling that I’m not really wanted in Germany. Or, even worse, that I’m only tolerated because I got lucky and happened to fit a particular random set of criteria.

I’m not the only one who feels this way. My foreign friends and I talk about this a lot – and I mean a lot. And if I get even the tiniest hint of that feeling, what must daily life feel like for people who aren’t in my extremely privileged position? For people who can’t “go back home” because their homes are destroyed?

What you can do

Print this poster and put it up in your city, your school, or your workplace.

If you have a startup and are in Berlin, sign this open letter to the BMI and add your logo to the Berlin Founders Unite! website.

Sign this petition on change.org to remove the posters.

Most importantly, simply let the foreigners around you know that you appreciate them and that you are glad they are here. Here are a few concrete things you can do to support the foreigners around you:

- Invite them to your house.

- Invite them to social events and introduce them to your friends and family.

- Ask them if they need any help with any paperwork, bureaucracy, or logistics.

- Ask them about holidays, traditions, foods, sports, media, etc. where they come from. Don’t assume that because you read a book, or traveled there once, you already know everything – you will definitely learn something new and interesting.

- Tell them about German holidays, traditions, foods, sports, media, etc. Sure, it’s normal to you that a show with a mouse explains how machines work, and that Bielefeld doesn’t exist, and that everybody watches the same movie on New Years Eve… but I’m here to tell you, as a foreigner, that all these things are actually pretty freaking strange. Getting an outside perspective on your own culture can be a lot of fun!

- If you read news about something happening in their country, tell them you heard about it, and then give them an opening to talk about it. It’s nice to know that others are paying attention to your homeland. But don’t start explaining their own country or politics to them! This can make them feel very alienated and lonely, because you’re almost certainly missing a lifetime of context.

- If you hear anybody say things that are discriminatory or anti-immigrant, even just a little, even just as a joke, say something. If you can’t think of the right words, just make a “what the f%#&k?” face and give the person a dirty look.

Let me know if there are other petitions or initiatives I should add to this site. (An obvious next step would be a directory of places you can volunteer and donate, but honestly that would be pages long and I just want to get this blog post up.)

Credits

Since I first posted on Facebook, over 100 people have contributed translations, or asked their friends to contribute translations!

On December 7, 2018, a group of us gathered for a little Glühwein and civil disobedience:

The pomegranate illustration is by fellow foreigner Mana Taheri; pomegranates are an important part of life in Iran, and they’re a big part of Yalda, the longest night of the year. We thought using less nationalistic and more meaningful imagery would give this poster a more human feeling.

Particularly big hugs and fist-bumps to Kathleen, Jan, Aurélie, Henning, Morganne, Abdel, Sahar, and Pooja for encouraging me to actually pull this together.

If you want to get in touch about this, you can email me at here@molly.is. Ich kann auch Deutsch, zwar nicht tadellos, aber es geht.